|

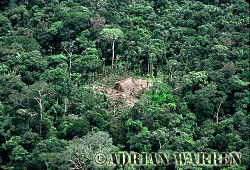

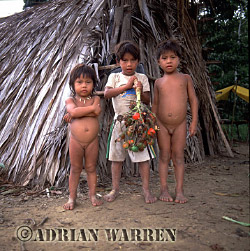

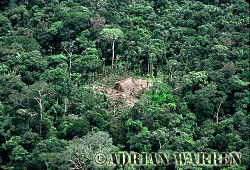

Traditional settlement (Home of Tagae), Ecuador, 1993 |

Tagae's isolationist group are the only Waorani clinging, because of their fears, to the old lifestyle in the forest, still aggressively reacting to any attempt at contact. In 1993, two tourists disappeared close to Tagae's house; only their boat and belongings were recovered. In the same year, there was news of a German photographer who was trying to visit Tagae's group, offering large sums of money to other Waorani to help him. Outsider pressure was piling on the stress and re-igniting old inter-family feuds. Shootings and killings were routine: the military shot three Waorani; a tourist guide apparently killed another; some Waorani kidnapped a woman from Tagae's group; and when they took her back, they were ambushed and one of them was killed. More recently, in 1999, a European student was injured in an attack, but managed to escape, the first ever to get out alive. Tagae's group continue to terrorise and to kill colonists who wander too close to their territory. The future for Tagae's group is a tenuous one, and it is difficult to say for how much longer they can continue to hold out.

|

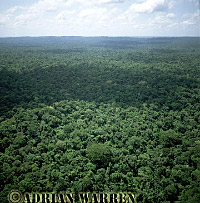

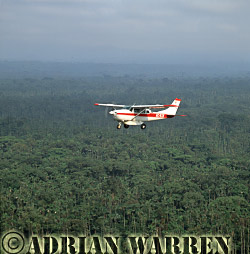

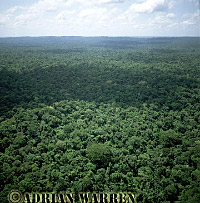

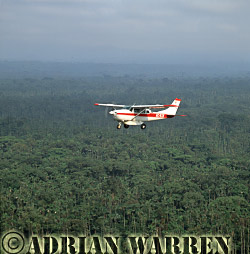

Rain Forest, rio Cononaco, Ecuador, 2002 |

Refugees from the Colombian drug and guerilla wars are also streaming into Ecuador. Conditioned to intense aggression as the only way to survive, many hold strong disdain for any indigenous peoples. Consequently, they start to grab Waorani lands and threaten to kill anyone who stands in their way. One Colombian colonist pointed a shotgun at the chest of a Waorani woman; three times the trigger was pulled, and three times it failed to fire. Her assailant simply walked off down the trail to his home, leaving the terrorised woman and her family too frightened to do anything about it.

There is also a more subtle but equally destructive process that threatens Waorani survival; outside tribes are now aggressively seeking Waorani spouses, so they can obtain right to Waorani lands, timber, game and fish. After contact, the Waorani quickly learned that marrying cowode brought significant benefits. A Waorani family married into a Quichua family would have access to outside goods and, especially, a place to stay during visits to the outside towns. But this system of reciprocal privilege also brought obligations. These cowode relatives gained the right to hunt and fish within Waorani territory, often carrying out hundreds of pounds of rain forest meat they have shot, or smoked fish they have poisoned or dynamited from Waorani rivers. Many have now built homes and planted gardens within Waorani lands, opening the land to even further exploitation as they bring in more relatives.

|

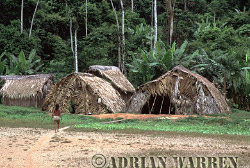

Caempaede hunting with Blowgun, 1983 |

Caempaede's group continues to live, in a more or less permanent settlement, by the oil company airstrip on the Cononaco river; he is now less dependant on traditional skills although he decries the loss, and his grandchildren, like Iyowa, are now more interested in learning Spanish and integrating into the culture of the outside world. They, like the remaining 1,600 or so Waorani, most of whom now live on traditional lands deeded to them by the Government of Ecuador, do not understand the difficulties that they face. Deeded land is not protected against colonists or mining activities. It is not enough to learn to speak, to read and to write Spanish; they will have to compete in a fiercely aggressive, uncompromising outside world which is totally alien to them. That is why, tragically, so many will probably become losers. Long ago, the Waorani concluded that to protect their own interests and survive in today's world they needed to learn the national language of Ecuador, Spanish. They appealed to the government to send in schoolteachers. But, like the roads, the schools have presented the Waorani with a serious dilemma. The schools have been the most aggressive and dramatic source of permanent change in Waorani culture. The teachers have enforced change, openly demeaning Waorani traditions and values. But, even more significantly, because children from the age of four are in a classroom, they do not spend time in the forest or with their families. They are becoming isolated from their traditions, and their connection with their environment is being lost.

|

Caempaede hunting with Blowgun, 1983 |

|

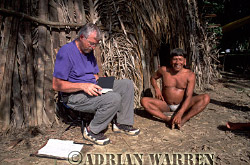

Caempaede and Jim Yost, 1983 |

The Waorani want to adapt and to survive in the face of the changes, and they are making progress. Their organisation ONHAE is actively seeking international grants, training, and fighting for their rights. They are looking for ways to create a sustainable economy. The Waorani are survivors and are trying to flex with the massive changes around them. They are confronting issues unknown to the tribe scarcely a decade ago: they have moved from an egalitarian society, with no formal leadership, to a society that is learning to utilize Western practices and institutions, like grants, law, and education, in order to try to maintain their own dignity and integrity in the face of severe pressures. As a united people, the naive forest dwellers of a generation ago are becoming quite adept at political maneuvering, even in the face of huge global corporations. In an effort to discover less destructive sources of income, the Waorani are aggressively seeking to develop ecotourism. They have travelled to the USA, to Peru, Brazil and Costa Rica to learn how to develop it. For generations, rumours and fears of potential hostilities from other villages fuelled violence. But when the Waorani gained access to faster travel, and especially to the instant communication possible through two-way radios, they were able to address the rumours and fears more effectively. Today, two-way radios are pivotal in preventing violence, as one village knows what the other is doing, keeping suspicions down. The Waorani have learned that roads not only give them easy access to the outside, but they also give the outside easy access to them - to their land and its resources. To avoid this outside exploitation, they are rejecting more oil company roads, turning to river travel with outboard motors. They have also built thirteen airstrips scattered over their territory. Symbolic of their pride, confidence, and initiative they are now actively seeking their own aeroplane and pilot training.

|

|

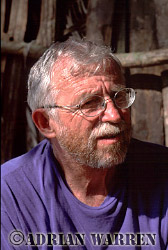

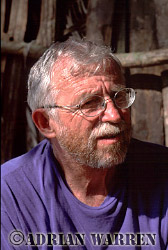

James (Jim) Yost, 2002 |

Caempaede, 2002 |

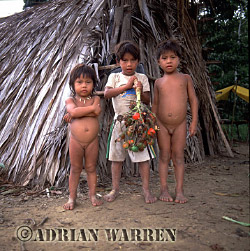

Jim Yost, among the first to make peaceful contact with some of the more remote Waorani, continues to make regular visits to his Waorani friends. Most recently, in January 2002, he gazed out of the window of a small Cessna aircraft from the Missionary Aviation Fellowship at the familiar thatched huts below as it circled overhead Cononaco airstrip. Banking steeply, and descending through gaps between the tall trees, the Cessna landed on the bumpy airstrip, where it was quickly surrounded by excited Waorani, among them Caempaede. Jim was affectionately greeted as one of the family.

|

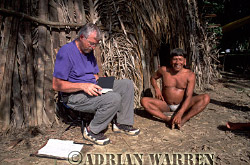

Jim Yost and Caempaede, 2002 |

Like so many times before, Jim and his Waorani friends walk towards the huts. As the plane departs, Caempaede and Jim, sitting outside a traditional house, remember old times. Caempaede remembers vividly what happened to his mother and father: when a child of a neighbouring family died and the father decided that it was the work of evil spirits sent by Caempaede's father, two of the neighbours came in the night and speared both his parents to death. It led, as usual, to violent retaliation; a vicious circle of feuds and vendettas. Caempaede's wife Minimo remembers watching both her parents being speared to death in broad daylight. They talk about these devastating events freely; the Waorani were used to spending their lives in fear of each other, and they were terrified of outsiders too, although when they discovered that cowode were not cannibals, they became curious to know more about our way of life. Through discussions with other Waorani groups at the Protectorate who had come to know a man called Jim Yost, they realized that he was a man who could be trusted; so, when contact was made, Jim was accepted warmly and given a Waorani name: "Wadica". So he came to live with the Waorani on and off for ten years together with his family, learning to speak their language fluently, getting to know their culture, and subsequently becoming the foremost authority on the tribe.

Jim Yost visits his Waorani friends at least once a year, rekindling friendships and keeping track of all the individuals and communities he has come to know and love through nearly thirty years of his life. During those thirty years, the Waorani have transitioned many centuries of sociological evolution. Embracing those gargantuan changes during a mere generation of Waorani, a bemused Caempaede, who is now over seventy years old, watches the surrounding world in the declining years of his life.

|

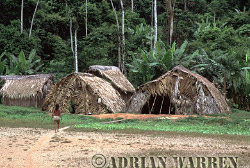

Rain Forest near Shell Mera, rio Cononaco, Ecuador, 2002 |

(7,893 words)

© Adrian Warren, Last Refuge Ltd., March 2002, in association with Dr. James Yost.