|

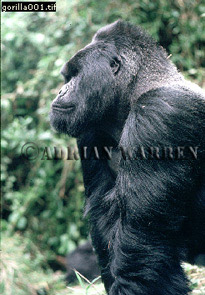

MOUNTAIN

GORILLAS

by

Adrian Warren

Mountain Gorilla (Gorilla g. beringei), Virunga

Volcanoes, Rwanda

A number of expeditions

followed, notably that of Carl Akeley who, in 1921 went to the Virunga

Mountains to collect Mountain Gorilla specimens for a diorama exhibit

in the American Museum of Natural History in New York. His expedition

team included an eight year old girl, Alice Bradley and he documented

the adventure not only with still photographs but also with a 35mm. movie

camera which he designed and built himself. With that camera he took the

first ever movie shots of Mountain Gorillas. The killing of his first

gorilla, a silverback which he called "The Old Man of Mikeno"

after the mountain of the same name, was not only a turning point in Akeley's

life but also in the destiny of the mountain gorillas. Looking into the

dead gorilla's face, he had a change of heart. Recognising their closeness

to us, their intelligence, and their gentleness, he didn't want to kill

any more. He also recognised their apparent rarity and, therefore, the

need for research into their natural history. His party collected five

gorillas which still form an important exhibit in New York. Following

his expedition, Carl Akeley urged the Belgian Government to set up a permanent

sanctuary for the mountain gorillas, and became instrumental in the establishment

of the Albert National Park on 21 April 1925, and on 9 July 1929 the boundaries

of the Park were extended to include the entire Virunga volcano chain.

Seventy years later, the

volcanoes are still protected, though divided by the political boundaries

of Zaire, Rwanda and Uganda. Today, the gorillas' home is an island surrounded

by cultivated land inhabited by one of the densest population of people

to be found anywhere in Africa. In January 1991, standing on the rim of

the volcano called Visoke, at around 11,400 feet above sea level, I had

a spectacular view of the forest and the line of volcanoes but the view

also showed me the stark line between the forest and the endless cultivation;

it made me appreciate the isolation and fragility of this tiny piece of

pristine land. With me were George and Kay Schaller, returning here after

an absence of thirty one years. While we were standing there, breathing

in the wonderful unpolluted air and surrounded by that very special community

of African sub-alpine plants, including giant Senecios and Lobelias, we

could hear intermittent gunfire to the East. The latest round of squabbles

between humans trapped by overcrowding problems and obsessed by survival

and greed seemed to underline the pathetic and hopeless future for the

land on which we stood.

It is to this forest that

George and Kay came, in 1959, to conduct the first exhaustive field study

of mountain gorillas. George used to do all his own tracking, following

the trail of beaten down vegetation, smelling the fresh droppings and

touching them to see if they were warm or cool. "Finally, far ahead

I would hear a branch snapping, then a sort of grumbling sound and then

I used to look for the nearest tree, not to escape but to climb up high

enough to look down on them. A couple of times I made a mistake and found

myself right in the middle of the group with gorillas all around me -

the interesting thing was that they seemed to realise that I'd made a

mistake and that I wasn't the least bit aggressive. I used to back away

and the gorillas would continue their daily routine. Occasionally a male

was annoyed at my presence and roared and beat his chest. It is interesting

that I was never once charged by a gorilla, partly, I think, because I

didn't push them". By observing from a tree, George gained the gorillas'

confidence since they could see him clearly and he had a better view for

making his observations. Down below, he could approach much more closely

to the gorillas, but never get a good look at one. "You can hear

branches breaking, sometimes you see a black arm reaching out but although

you know much interesting behaviour is occuring you can't see it because

of the dense vegetation". George would stay with his study group

all day, and often all night too: "towards dusk, the male would go

somewhere to start building his nest, and the others would all go and

start building nests, I would blow up my air mattress and lie down near

them and sleep pulling a tarp over my head, staying with them until morning

when I would watch them awake, stretch their arms, yawn and start eating.

It was wonderful to get into the daily routine at their speed, not my

speed; trying to adapt to their rhythm of life - that was one of my great

field experiences". In little over a year of dedicated and painstaking

work ,the Schallers made huge advances in our knowledge of gorillas and

their behaviour, and the results of that research are still regarded as

the "bible" for those who have followed.

Dian Fossey's Cabin,

Karisoke

research centre, Rwanda

The late Dian Fossey,while

not recognised as a high calibre field biologist, did much to bring the

plight of a dwindling population of mountain gorillas to world attention

during the nearly nineteen years that she spent involved in their research.

Her work began, in 1967, in Zaire, but due to an unstable political situation

she soon moved to Rwanda where she established her research centre high

up on the shoulder between two volcanoes, Karisimbi and Visoke, putting

these two names together to call her base "Karisoke". Dian devoted

herself to the habituation of gorillas to make it possible to observe

them at close quarters; in this she was extremely successful, becoming

the first person to have "friendly" physical contact with a

wild mountain gorilla when a young male she called "Peanuts"

approached her, then reached out and touched her hand. That moment set

in concrete her emotional bond with the gorillas: she became obsessed

with protecting them against the onslaught of the outside world, putting

a stop to cattle grazing in the Park; trying to prevent the capture of

gorilla infants for zoos, an extremely disruptive process which usually

resulted in the death of the infant's mother and put the group into social

disarray; and taking controversial action against poachers who, until

1985, were hunting and killing gorillas to provide heads and hands as

grisly souvenirs for tourists. The brutal killing, and dismembering, of

one of her favourite research animals "Digit", in December 1977,

only served to increase her bitterness and resentment against those whom

she thought were out to exploit gorillas. In January 1978, she established

the "Digit" Fund to help financially support Karisoke Research

Centre and gorilla protection work in its vicinity.

|